Researchers trudging down the long and twisted path toward an AIDS vaccine are encouraged by new studies that show an experimental vaccine protects monkeys against infection with a virus that is very similar to HIV.

The vaccine protected 80 percent of monkeys from infection with SIV, the simian version of HIV. By comparison, an experimental HIV vaccine was 31 percent effective in protecting people against infection in a large-scale study unveiled in 2009.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute on Allergies and Infectious Diseases, tells Shots the monkey studies, published online in Nature, are important for several reasons.

First, the virus used to challenge the monkeys after vaccination was "a pretty hefty, robust" virus, as Fauci puts it. In the past many studies used the same virus both to vaccinate animals and then to infect them. "That's stacking the cards in your favor," Fauci says.

The new study is more of a real-world test of a vaccine, because people are likely to encounter viruses that are not genetically identical to the ones used in the vaccine.

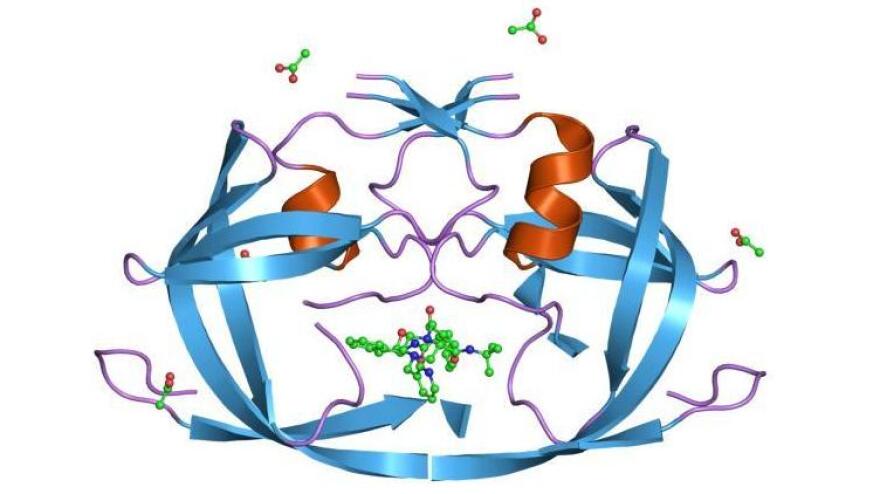

Another stand-out aspect of the new study — arguably the most important one — is that it nails down what sort of immune response an AIDS vaccine will need to prevent infection. Specifically, the vaccine must stimulate the immune system to make antibodies against a specific part of the virus's envelope, or outer coating, called the V2 loop.

This is not the classic type of antibody that scientists generally think is necessary to "neutralize" a virus. The 2009 human vaccine trial hinted that antibodies against the V2 loop were important, but the evidence for that was sketchy.

"This study makes it very, very clear," Fauci says.

The monkey paper also shows clearly that a vaccine must stimulate two different kinds of immunity — one to guard against infection, the other to damp down the virus if infection occurs anyway.

The new studies were led by Dr. Dan Barouch, a vaccine researcher at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

One note about the 80 percent protection seen in the monkeys: It means the vaccine reduced infection by that much when the researchers inoculated the animals with a single relatively high dose of the virus. After repeated exposures, virtually all the monkeys eventually got infected despite vaccination.

In the real world, of course, humans get exposed repeatedly to HIV, so a vaccine would need to protect over time. But Fauci points out that in the real world, each exposure would involve far lower doses of HIV.

In the end, the only way to know how protective an experimental AIDS vaccine is for humans is to test it in people. The Boston group is raising the $22 million it will take to do the initial safety testing in humans. It might begin next year.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.