The world's fastest supercomputers have come back to the U.S. In June, the title was claimed by a machine named Sequoia at Lawrence Livermore Labs. Monday, at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, what could be an even faster computer comes online. It's called Titan and it would not have been possible were it not for the massive market for video games.

The first thing you notice when you visit Titan is the noise. The room reminds me of a 1980s-era Kmart — but much louder. The room is very large, about a half acre. Big stainless steel pipes help keep Titan cool. The pipes have been repurposed from the dairy industry, which is not surprising considering that Cray, the company that built the computer, is based in Wisconsin. Cray built special fans to cool each cabinet. The fans are so powerful the floor in the room vibrates.

All of this complicated engineering is in the service of speed.

Titan is quite possibly the fastest computer in the world. We won't know for sure for a few weeks, but Titan is designed to do more than 20,000 trillion calculations a second.

That's faster than half a million laptops. But it's not cheap. This machine cost $100 million. Its electric bill will total $9 million a year. So what makes all this computing worth the price?

"It gives us more fidelity," says Buddy Bland, who runs the leadership computing facility at Oak Ridge. "We're trying to simulate the real world, the physical world, on these supercomputers. And if you think of them, they're really a time machine that [lets] us look into the future and understand what's going to happen."

Higher fidelity and higher-resolution models mean scientists can begin to predict things like climate change locally and regionally.

"At the high resolution things like hurricanes and typhoons actually start to show up that never show up when you run the exact same simulation at just a lower resolution," Bland says. "That's an important outcome that policymakers need to know about."

Researchers will compete for computing time on this machine. It will be used to model everything from biochemistry to black holes to nuclear reactors.

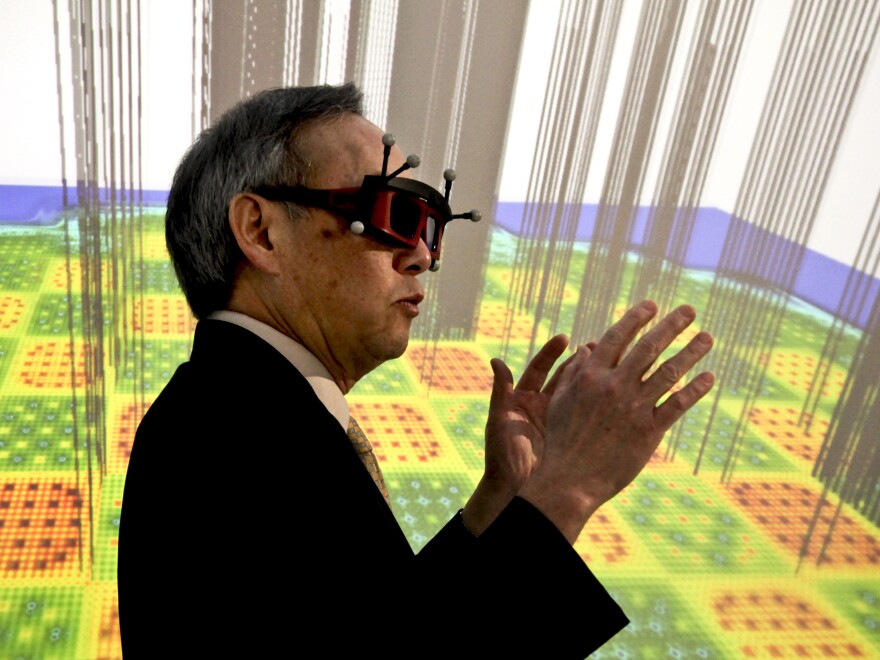

"My group is interested in understanding the molecules of life and we also want to understand how they wiggle about," says Jeremy Smith, a biophysicist at the University of Tennessee and Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

He hopes that by screening libraries of small proteins against known receptor sites his team could find new drugs for Parkinson's disease and prostate cancer. "Until now we've been able to do that with a few thousand small molecules, but with the new upgraded supercomputer we'll be able to do tens of millions of these molecules," he says.

And Smith fantasizes about an even faster machine — one that could screen for side effects, too. But there is a problem. In the past decade the traditional methods of making supercomputers faster hit a wall — the power wall, Bland says.

He says for years you made microchips speedier by giving them more electricity. But Bland says there's just not enough cheap electricity to power the kinds of computers scientists like Smith dream about — one that's 50 times faster than Titan.

"If we used today's technology it would take two gigawatts — it would take two nuclear power plants to power it," Bland says.

So over the last few years supercomputing engineers have found inspiration in an unlikely place — video games.

In today's games the graphics are intense — virtual water reflects and refracts virtual light. The rules of physics apply and dozens of people can play these games together.

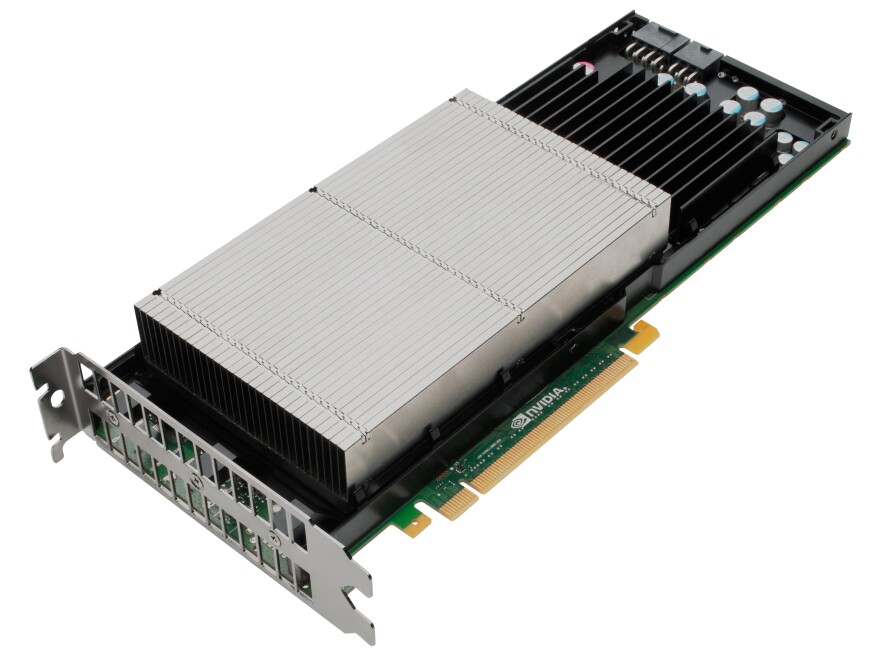

"Every object in that game is actually being modeled in 3-D," says Sumit Gupta, who runs accelerated computing at Nvidia, a company that makes chips designed for gamers. He says modern games require immensely complex calculations. "And you have to do billions and trillions of them per second," he says.

Bland and Gupta say chips built for games consume much less power.

And, Bland explains, "it turns out the types of calculations that they do to make those beautiful visualizations are very similar to the types of calculations we need to do to, for example, do climate simulation."

That's kind of the way conventional computer chips work — if you want to go faster you have to step on the gas. Graphics chips are different. They work in parallel.

"A pretty simple analogy that I always use is that when [my wife and I] go to the grocery store, we sit in the car, we drive a certain path and we reach the grocery store," Gupta says. "Once we get to the grocery store, my wife and I can simultaneously go through the aisles picking up stuff."

That's how gaming chips go faster.

Today video games are a $30 billion industry. And it's pushing graphic chip designers to build faster and faster chips. Scientific supercomputers are hitching a ride, which is why Gupta says we should all let our kids play those video games.

"Absolutely — except my kids," he says, laughing.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.