It says a lot about the state of the war against poachers in Africa that the Lewa Conservancy, a private sanctuary in Kenya with 12 percent of the country's rhinos, recently appointed a CEO who has never studied zoology or biology. Instead, Mike Watson is an ex-captain in the British army.

His training has already come in handy. Take, for instance, a visit to a crime scene earlier this year: a rhino carcass splayed out in the mud.

Watson holds a black-and-white photo, a kind of rhino mug shot. Kenya has only about 1,000 rhinos, and each one is branded with a distinct pattern of ear notches and registered in a countrywide database. Watson is able to use the photo to identify the dead creature. His name is Arthur.

Even if we improve the fighting force, they will still outdo us because the price for rhino horn has risen so significantly."

According to his papers, Arthur was a 4-year-old black rhino. Flies now buzz around the bloody socket where his tiny horn once grew. Arthur's fatal mistake was coming back to visit his mother. The extra noise of two rhinos chewing very likely tipped off the prowling gunmen, who fired 23 rounds from an AK-47 from a ditch about 10 yards away.

There's a village nearby, just beyond the sanctuary's electrified fence.

Residents say they didn't hear anything, nor did the guards at their observation post a half-mile away. Watson says that suggests the killers used a gun with a silencer.

They were probably using night vision goggles, too, since the shooting happened under a new moon in the pitch black. Arthur was the sixth rhino killed in four weeks.

"If we don't do something, we're going to lose all our rhino," Watson says. "Kenya's going to lose all its rhino."

A Military Approach

For the past 25 years, the strategy for protecting rhinos has essentially been "contain and defend." Rhinos do like to wander, but unlike elephants, they don't actually migrate.

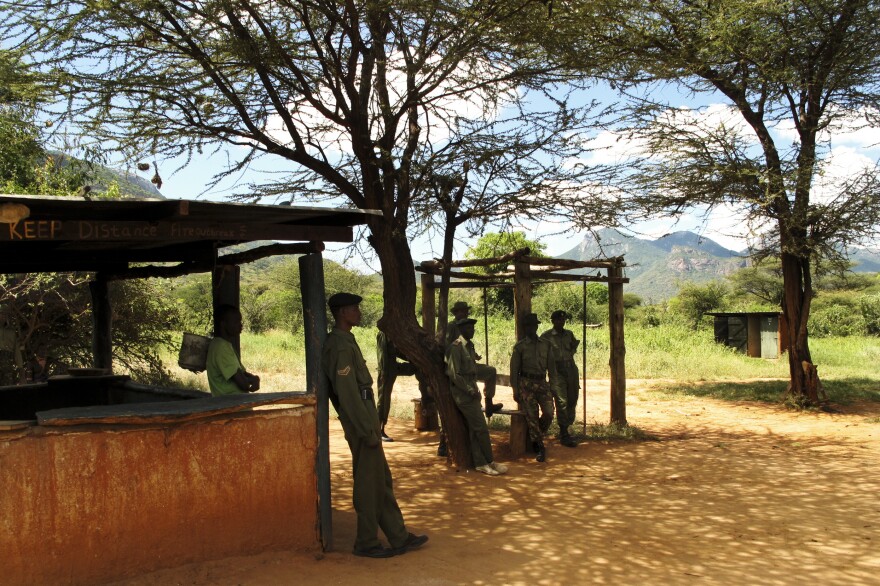

An electric fence surrounds Lewa's 62,000 acres of savannah, which is defended by a $1 million-a-year security outfit that includes armed rangers, night trackers, dog handlers and a helicopter. (Not to be outdone, its sister conservancy, Ol Pejeta, will soon get its own drone.)

But this very security apparatus has, in some instances, been used to kill rhinos instead of protect them. Lewa's armed rangers have been paid off by poaching cartels, and its sophisticated location tracking has been used by staff members coordinating with poachers.

Patrick Omondi is head of species for the Kenya Wildlife Service, the government branch responsible for protecting wildlife. For several minutes, he ticks off all the new equipment he has requested, including thermal vision goggles and tracking chips embedded in every horn.

But even Omodi doubts that a military approach on its own will stop the slide.

"Above all is the issue of demand reduction; we need to look at [that]. Because even if we improve the fighting force, they will still outdo us because the price for rhino horn has risen so significantly," Omondi says.

An African Prize

Rhino horn is literally worth its weight in gold in Vietnam, where the demand for powdered horn has grown dramatically — both as a status symbol and as a traditional medicine. In fact, in recent years, it has traded at a price as much as that of gold, $1,400 an ounce.

And unlike so many other wildlife products stolen from Africa and smuggled to Asia, a good chunk of the money spent on rhino horn actually returns to the poacher. That's not the case with ivory. While ivory can garner many thousands of dollars in China, an elephant poacher in Kenya might only be paid $600 per tusk.

Operational secrecy is compromised. It's not rampant and endemic, but we've got people on the inside who are feeding information, which makes it doubly difficult to do the job."

The same poacher could clear $40,000 or more for a rhino horn.

And that's just for the poacher. Forget the syndicates up the chain in Asia that might unload it for five times that. The street value of just the 125 rhinos at Lewa is $10 million.

This difference in the profit margin is one reason the rhino poacher and the elephant poacher — though often conflated in news reports — are totally different species of predator.

"With a rhino poacher, the risks are massive compared to an elephant poacher," says Ian Craig, founder of Northern Rangelands Trust. He is one of the few conservationists in Kenya who have talked with both types of criminal.

Craig says rhino poachers have vastly more money at their disposal. Their task is also exponentially more difficult, with all the rhinos in the country living in sanctuaries guarded by armed rangers who will shoot to kill if fired upon.

"The time frame for killing a rhino, taking the horn and getting away with it is so narrow," Craig explains — about a half-hour, he says, compared with a couple of days for an elephant poacher to shoot his prey and steal the tusk. So as a practical matter, considering the size of Lewa and how rhinos are spread out, the poacher would have great difficulty succeeding without inside information. Watson, Lewa's CEO, says he is now certain that some of his own employees assisted in the killing of Arthur and other rhinos.

"Operational secrecy is compromised," Watson says. "It's not rampant and endemic, but we've got people on the inside who are feeding information, which makes it doubly difficult to do the job."

And when he realized this, he says, it took him right back to a lesson he learned in the British army: All the helicopters and all the weaponry in the world cannot win a war without on-the-ground intelligence.

Fighting Back

That's when Lewa developed its own spy network: an affiliation of informers in the surrounding towns and even inside Lewa itself. Watson also fired the suspected turncoats. That stopped the killings, for a spell.

John Palmeri, chief of security, says now they have a new enemy: the cellphone. If one of their rangers simply calls a poacher to alert them — say, there's an unguarded rhino in the northeast corner — that phone call will be richly rewarded, reportedly to the tune of $3,500.

That's a lot of money for a rural Kenyan, especially for committing a crime for which no Kenyan has ever served prison time. They're all free on bail.

"This money is tempting people in the system," Palmeri says.

Does it ever tempt him?

"No. ... I came here when [there were 20 or fewer rhinos]. At the moment we have 125 animals here," Palmeri says. "And especially, if you have been here, growing with these animals, and knowing that [the animals] have reached this number because of me."

Not every ranger has such a personal link. Some are just here for the job. So the poaching crisis has left every conservancy in Africa with a question that any army fighting a guerrilla war hates to confront. It's not how to defend; it's whom can you trust.

Just recently the last rhino in Mozambique may have been killed, and if so, it was apparently with the direct assistance of the game rangers protecting it. The warden of Limpopo National Park recently told the Associated Press that he'd caught members of his staff "red-handed while directing poachers to a rhino area."

And considering how much money is dangling there on the black market, it's remarkable that more rangers haven't been turned. So while it's true that rhinos are losing the war against poachers, it's also true that they have a surprising number of loyal friends.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.