By Claudine LoMonaco

http://stream.publicbroadcasting.net/production/mp3/knau/local-knau-901235.mp3

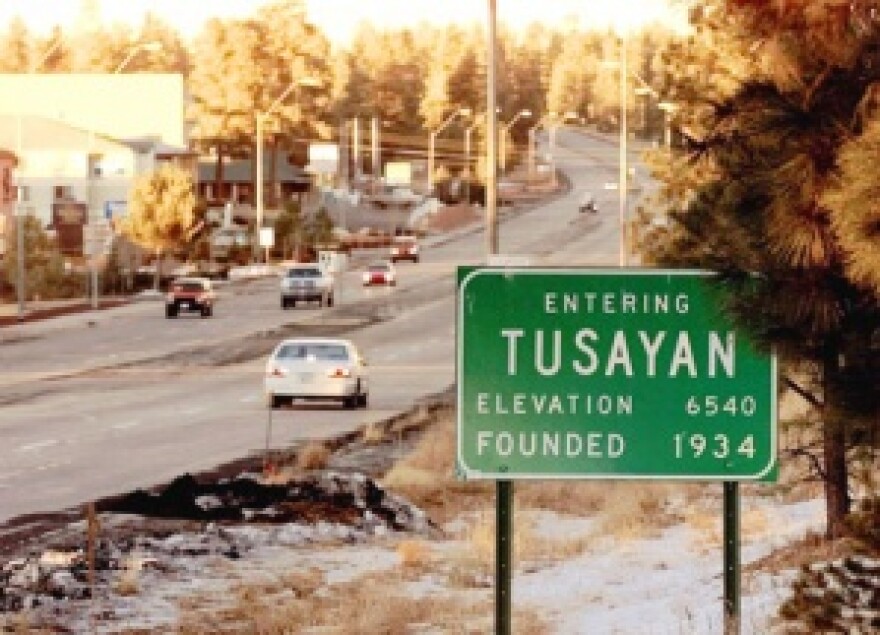

Tusayan, AZ – Tusayan isn't much to look at. A half-mile strip of highway lined by hotels nestled in ponderosa pine forest. But it has one very big thing going for it- it's just a mile from the entrance to Grand Canyon national park.

Tourists spend millions of dollars every year- on everything from helicopter tours to pancake breakfasts. Tusayan's economy depends on that money, but some want to bring in even more.

"Right now, there are two and three star offerings. Is there demand for four and five star offerings? Retail services, outdoor cafes? A piazza?

You heard right. A piazza. That's Thomas DePaulo. He represents a group of Italian developers who own a lot of land in the area. Over the years, they've proposed building an outlet mall and a controversial thousand-room resort called Canyon Forrest Village.

The Park Service backed the resort plan because they wanted to move development away from the canyon. But many worried the hotel would tax the area's fragile water supply.

Others worried about increased competition. Clarinda Vail owns the Red Feather Lodge.

"Can that many more rooms come on the market and not put hotels out of business."

Ten years ago, Vail rallied voters in Coconino County to reject the resort.

But the developers didn't give up. They teamed up with a competitor of Vail's and launched a campaign to incorporate the community of Tusayan as its own town, with its own town council. That way, they'd only have to persuade 5 council members to approve their plans, not an entire county. Tusayan residents voted the plan down in 2008, but the developers got it back on the ballot this March.

Miguel del Billard works in one of Tusayan's gift shops. He says backers of incorporation promised better jobs and a chance to own his own home.

He points to a mobile home where he lives with five other men. Like most of the other low wage workers in Tusayan, he lives in housing provided by business owners.

He says that he'd love a house, but he wonders how he or of his fellow workers could possibly afford it.

To get their message across, the developers flooded YouTube with slick, highly produced commercials:

The no side fought back with Michael Moore style clips that attempt to unmask the foreign influence.

But it was no match. The Italians developers spent more than three hundred thousand dollars to persuade about 200 voters and they won. In March, Tusayan officially became Arizona's tiniest town.

But the election left deep wounds.

Eric Guissaz co-owns and cooks at the town's only diner. He said Tusayan used to be a friendly place:

"Before the incorporation topic came up, people would say "Hi, how you doing." To me, it was civil."

Now, he says, people shield their faces and turn away.

"There are people in this town that I will never address again because of that."

Guissaz opposed incorporation. Ironically, he supported it 10 years ago when locals thought it might be their only chance to defeat the Italians. But back then, he says it was out of a true, democratic impulse. Now he says it's just a tool to further development interests.

"Why would anyone allow for some foreigners to come here and tell us how to run our lives just because they have pockets lines with money?"

If the Italian developers were hoping for a green light on projects any time soon, they're probably out of luck. As it turns out, Coconino County appointed an interim council last month, and it's evenly split. Two members opposed the incorporation, two supported it. The fifth member claims neutrality. He works for a major incorporation backer, but is married to an anti-incorporation leader. The town will vote for permanent members in November.

That's if the town survives incorporation that long. Because the election was held so late in the fiscal year, Tusayan only has until July 1 to figure out how it's going to raise around two million dollars to pay for services the county used to provide.