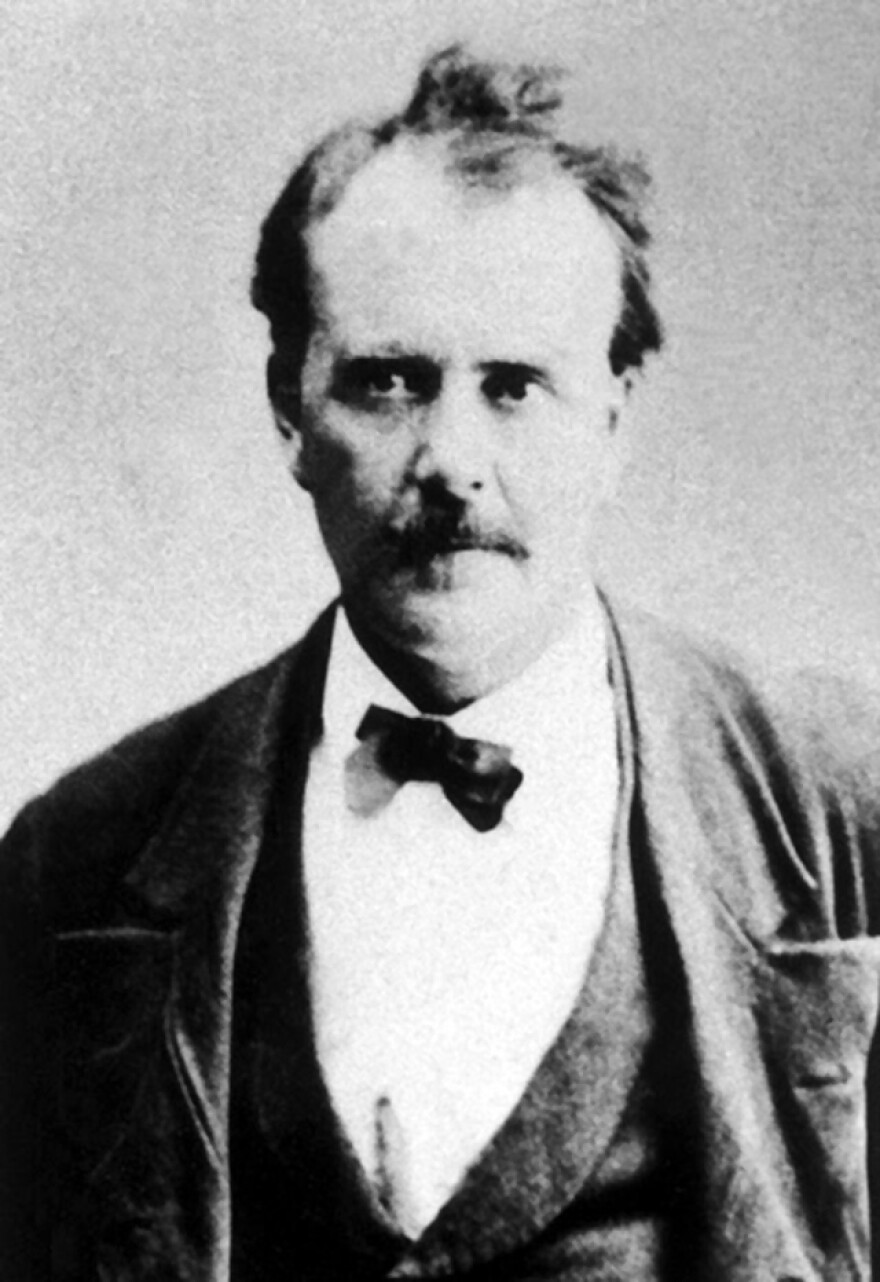

An old newspaper account caught the eye of commentator Scott Thybony. It described a grueling 19th century Grand Canyon trek taken by frontier lawyer Wells Spicer to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. It turns out that he also played pivotal roles in the two most famous court cases in the American West. Thybony tells Spicer’s story in this month’s Canyon Commentary.

The life of a single person links the Mountain Meadows Massacre, a secret gold mine, and the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. But what first drew my attention to Wells Spicer was something closer to home. To my surprise, the frontier lawyer had conducted an early exploration of the Grand Canyon backcountry. In 1875 he stood on the rim 3,000 feet above a dramatic convergence of rivers. Following rumors of a hidden mine, Spicer descended to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers.

The route plunges through cliffs requiring several hand-hold climbs, followed by high-angled talus and sketchy traverses. My step-by-step knowledge of the route came from having done it bent over, carrying a ninety pound boat on my back. A misplaced sense of adventure, I guess.

Near the mouth of the Little Colorado, the lawyer reported “a great ledge of rock salt cropping out in the walls.” This was where the Hopi gathered salt on their journey to the Grand Canyon. Returning to the rim Spicer wrote, “It was with the greatest difficulty that I climbed back. It was as hard a day’s work as I ever did. I was lame for a week afterwards …” A common condition among canyon hikers.

Wells Spicer was a journalist, a mining speculator, and an attorney who practiced in what was then Utah Territory. On good terms with the local Mormons, he had agreed to represent the notorious John D. Lee. His client had been charged with murder committed during an attack on a wagon train where more than 120 emigrants lost their lives. Spicer advised Lee to make a full confession but he refused. The trial became national news and ended in a hung jury. The second trial was scheduled to begin a year later giving Spicer time to search for what Lee called his “hidden Treasure.” Spicer used a prospecting expedition as cover to find a mine that likely never existed.

After disappearing for ninety days, he sent a series of dispatches to a Salt Lake City newspaper. The lawyer recalled “the mighty and terrific cañons, chasms, crags and precipices of this country.” He admitted having chased “wild reports of gold and rich mines.” The sheer-walled gorge of the Little Colorado River, he wrote, “was highly grand and sublime, but no money in it, so we passed on.”

At his second trial the jury found John D. Lee guilty. Sentenced to death, he was taken to Mountain Meadows where Spicer witnessed his execution by firing squad. During the trials, Spicer had managed to anger both sides and found it prudent to leave Utah.

He headed into Arizona Territory and landed in Tombstone where he served as a justice of the peace. In 1881 Spicer again came to national attention as the arbiter of the most famous gunfight on the western frontier, the shootout at the O.K. Corral. The case was brought before Judge Spicer and lasted a month. In the end, he found Wyatt Earp, his brothers, and Doc Holliday fully justified in their actions as officers of the law. A cycle of violent retribution and revenge followed.

Spicer finished his term as justice of the peace and left Tombstone. A few years later he disappeared on a prospecting trip into the Sonoran Desert. The newspapers speculated that he had committed suicide or possibly went mad and died of exposure. Most likely, Judge Spicer had faced the ultimate judgement and died of thirst alone in the desert. And the memory of his pivotal role in two of the most famous court cases in the American West soon faded.

Scott Thybony is a Flagstaff-based writer. His Canyon Commentaries are produced by KNAU Arizona Public Radio and air on the last Friday of each month.