As the sun beams down, Dorothy Flood, 75, stands on the steps of the Royal Gorge Route Railroad train, smiling like a 1940s movie star.

"Right there! Then turn around, right there!" photographers call out, jockeying to snap her picture. "Here we go, count of three — one, two and three!"

And with a tip of his cap, a porter offers Flood his hand, and her "Wish Of A Lifetime" begins.

Many are familiar with the Make-A-Wish Foundation, an organization that grants wishes to terminally ill children. Less familiar is the nonprofit group Jeremy Bloom's Wish Of A Lifetime. The organization grants wishes to adults age 65 and older — and recipients need not be ill or dying to qualify.

Dorothy Flood's wish — to ride in a train dining car — is an easy one to make come true.

A Powerful Memory

On this sunny morning, Flood boards the train in Canon City, Colo., and is escorted to the first-class dining car of the Royal Gorge Route. The car is a masterpiece of oak, brass, glass and white linen. As Flood sits down at her table her eyes fill with tears.

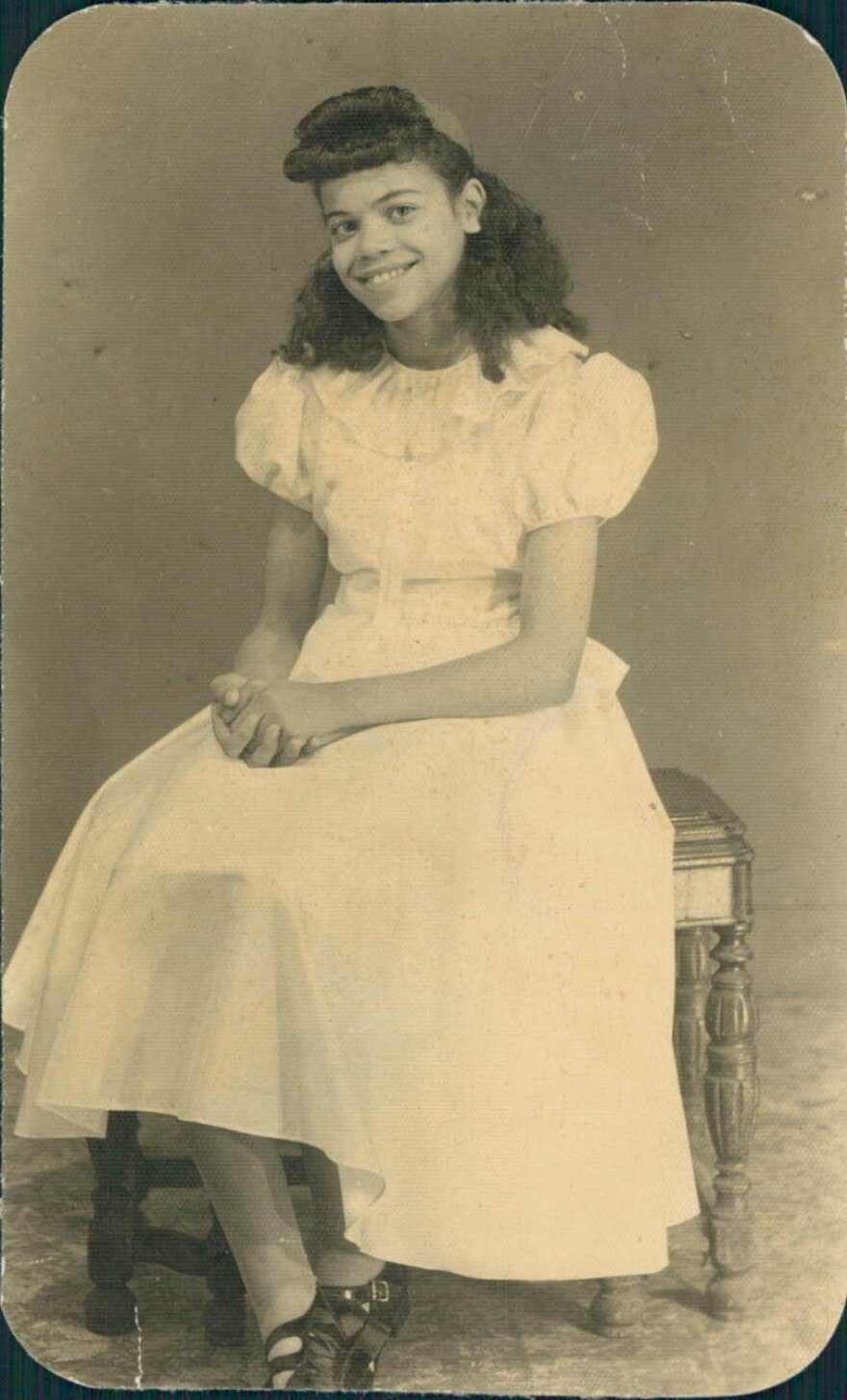

The vestibule door between the train cars and its intricately etched glass has conjured up a powerful memory. When she was 6, Flood was on the outside looking in through exactly that sort of glass. A little girl got up from her dining car table and came up to the opposite side.

"And she came up to the window and smiled. And then we just took our fingers and we were playing on the window. We would follow each other's fingers and play and laugh," Flood recalls.

Then, the girl's mother saw the pair, and called her daughter back. "So she smiled at me and waved goodbye, and I could see her running back," Flood says.

As she watched the girl skip away, Flood did not feel resentful or sad. Flood was on one side of the door because she was black. The little white girl was dining in the train's dining car.

The two girls were separated by Jim Crow and etched glass, but for a few minutes they'd been friends nonetheless.

Crossing The Mason-Dixon Line

Flood grew up in ethnically diverse Jersey City, N.J. But traveling by train to North Carolina each summer with her grandmother was like traveling to another country.

"When we'd get to Baltimore, that was the Mason-Dixon Line," Flood says. "The African-Americans would go in the back ... and white people would go into separate cars."

Flood and her grandmother — and many of the other black passengers — carried their food in shoe boxes.

"I guess that was the easiest thing to carry them in. And every shoe box would have fried chicken, pound cake ... a hard-boiled egg and fruit," Flood says. "And to this day it's the best fried chicken I ever had."

But while the food was good, the child, whose parents had been killed in a car accident, couldn't grasp why she and her grandmother couldn't eat in the dining car.

Flood would ask her grandmother why they weren't allowed.

"She said, we were people of color, so we weren't allowed to sit in there and eat," Flood says. "It didn't make any sense because I was going to school with them. I lived next to them. But now that I crossed that Mason-Dixon Line, I couldn't be with them? I didn't understand it."

Flood is of the last generation of African-Americans to grow up before the civil rights movement. Her perfect diction had nothing to do with "acting white" — the very idea was laughable, she says.

Mostly, Flood emulated her grandmother's quiet approach to the reality of their black skin. Although sometimes in North Carolina, she would chafe at the racism she perceived all around her.

She remembers one incident at an ice cream parlor, when she was around 8 years old. "I used to love milkshakes," Flood says. When asked what kind of milkshake she wanted, she replied, "a black and white."

"Everybody looked at me wide-eyed. ... The look that came on [my grandmother's] face was sheer terror," Flood remembers. "It was vanilla and chocolate — and I said 'black and white!' "

Her grandmother's frightened expression and the complete silence in the room was communication enough. Flood decided she wouldn't mock the monster again. Back in Jersey City, most of the time it wasn't an issue anyway.

Keeping Her Distance From The Civil Rights Movement

By the late 1950s, Flood was a young woman in college in Philadelphia. The civil rights movement had begun to swirl around her.

"I was never, like, part of that, the civil rights movement," Flood says. "Because I had never been blatantly ostracized, it didn't mean that much to me, and I couldn't understand it."

When James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality, John Lewis from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Martin Luther King Jr. called for a massive march on Washington in 1963, one of Flood's girlfriends suggested they go together.

The 8-year-old Dorothy Flood in the ice cream parlor would have jumped at the chance to participate. But the adult Dorothy Flood said no.

A half-century later, Flood says she's ashamed of herself.

"When I think about what people of color have gone through ... I'm glad I wasn't a part of it, but I wish I could have given more support," Flood says.

So when Flood's retirement home in Houston offered its residents an opportunity to win a "Wish Of A Lifetime," Flood entered the contest.

Soon after, she was on the train, a waiter swirling around her with a chilled glass of zinfandel and a white napkin on his arm.

"I can't believe it. I don't remember it being quite this elegant, but then again, I never was in there," Flood says of the Royal Gorge Route's dining car. "It's fabulous. And I know my grandmother's spirit — she's right here with me. She's probably smiling and laughing ... after all these years."

Flood's wish was all made possible by the largest retirement home company in the nation, Brookdale Senior Living, which is partnering with Wish Of A Lifetime. The organization was founded by former gold medal Olympian Jeremy Bloom.

Building An 'Appreciation For Seniors'

Rachel Greiman, a wish coordinator for the organization, says the program is about building respect for seniors in America.

"We don't believe that young people have an appreciation for seniors. So that cultural shift is something we're really trying to do," Greiman says. "And the vehicle that we're trying to create that cultural shift through is granting wishes."

The Royal Gorge Route Railroad winds through the Rocky Mountains along the Arkansas River. At one point, the staff tries to coax Flood to walk to the observation area to see a spectacular suspension bridge.

But Flood has zero interest. She has a second glass of zinfandel, warm French bread, salad on the way and a seat by the window in first-class dining. She and her grandmother's memory are going nowhere.

"Oh she would have loved this," Flood says. "She would have loved it."

Flood pronounces her almond-crusted salmon the best she's ever tasted — almost as good as that fried chicken from the shoe box, she says with a laugh.

Three hours after pulling out of the station in Canon City, Flood's wish is over. She says she will never ride another train: This is the way she wants to remember her last trip.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.