As a young girl growing up in Ajmer, a small town in the Western Indian state of Rajasthan, journalist and author, Yashica Dutt, 38, says that she was painfully aware of the many sacrifices her mother Sashi made. Her father, a government officer, earned a modest income, much of which he spent on alcohol, but her mother insisted on enrolling Dutt in the best of schools, even though it was a struggle to pay the fees and buy textbooks and uniforms.

To make ends meet, especially after her younger sister and brother were born, Dutt knew that her mother had hawked all her jewelry, sought the help of her father-in-law, took on tedious sewing jobs, and did everything she could to keep up the appearance that the family was well-off — like buying a pair of shoes for Dutt that lit up as she walked.

Dutt knew they weren't just pretending to be rich to show off. They were aiming to have an "upper caste aura" so no one would guess who they really were — Dalits.

In India's rigid caste system — a system of social division that ranks the status of individuals based on the kind of jobs they do, Dalits are among the most oppressed of castes.

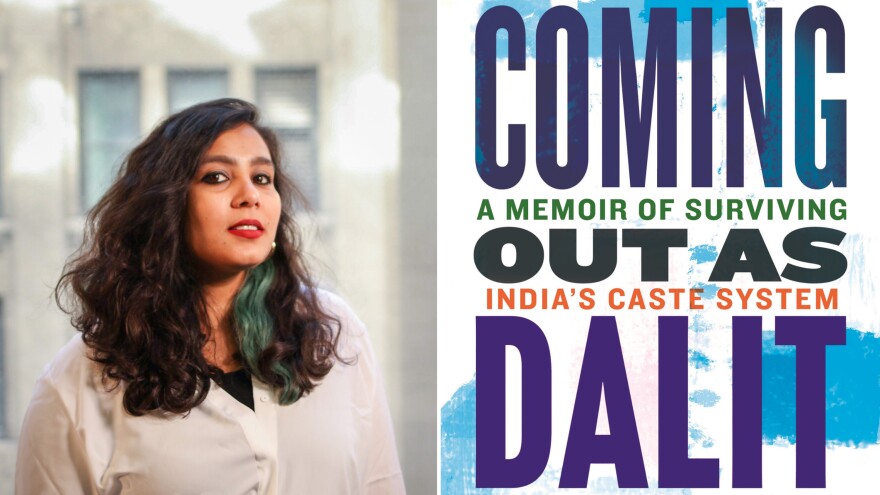

She tells her story in Coming Out As Dalit: A Memoir of Surviving India's Caste System, which was published in India in 2019 (and won a literary award). The book has now been released for the first time in the U.S., on February 6.

Dutt was always a top student in school but says she felt pressured by her mother's sacrifice and often humiliated by her begging the school administration for more time to pay her fees — even though she recognized that a good education would be her best defense against caste discrimination.

Dutt spoke to NPR about of the trauma of living with caste oppression and of her decision to speak out by writing of this book. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The word Dalit refers to someone belonging to an oppressed caste. Could you tell us about your caste specifically and the kind of discrimination the caste members face.

All Dalits are formerly [known as] "untouchables" — people who were outcasts, forced into the most dehumanizing professions.

I am from the manual scavenging Bhangis community — the actual name of my caste. My family's caste profession is to clean toilets. It's a degrading profession, because the work that we do becomes who we are. It becomes our identity.

And to give you some context, the very name of my caste is considered a slur by the Indian constitution — the worst insult you can hurl at someone.

The only way to survive these social structures is to hide.

Your way of hiding was to pass as an upper caste person?

Yes, racial passing has existed in the United States. We see similar practices throughout the world. For thousands of years, Dalits have been abused, mistreated, discriminated against and killed because of their lower caste. No wonder many of us hide our Dalit identity now.

Dalits in India have been passing as upper-caste Hindus by adopting elaborate lifestyle changes — changing their last names [that are linked caste identities], moving to cities, turning vegetarian, even embracing [the Hindu] religion — to appear more like upper-caste Hindus.

So keeping your dalit identity a secret was a protective mechanism. It must have been exhausting.

Absolutely.

Your daily life is a struggle to fit in. There's a high sense of hypervigilance — you're constantly monitoring your behavior. You can never be truly comfortable.

You have a sense of inferiority because you lack the caste privilege to belong in a certain group. You spend your entire life trying to overcome that lower status that has been foisted upon you. What I didn't understand at the time is that there's nothing I can do that can undo that. You cannot move out of your lower caste. You can obscure it but cannot escape it.

Is it possible to escape caste discrimination when your monetary status changes — for instance, when you land a well-paying job?

If there's anything we understand about systems of oppression, whether we think of race or caste, they don't go away with resources — or access to wealth. When I moved to the U.S. in September 2014, I was [studying art and journalism] at Columbia, which has a very robust South Asian and Indian American population. One of the things I heard people talking about [after she revealed her identity], was "How did that Dalit girl get into Columbia?"

You point out in your memoir that the attitude toward affirmative action — reserving a place in schools and colleges for people from oppressed castes — is often viewed by many as doing them a favor when clearly it is to correct a historical wrong. Can you elaborate?

When he was a kid, my great grandfather wasn't allowed to touch books.

He couldn't access classrooms and he couldn't use a slate [blackboard] because his touch would be considered "polluting" it. He had to sit outside and scrawl the alphabet in the mud with a stick.

After being barred from education for generations, now when we try to make up for it, we enter schools and colleges, only to face enormous discrimination. There's a culture of resentment — as if we're being given an unfair handout.

After hiding your caste identity for years, what made you expose it all with this book?

For me, the biggest understanding of my caste identity happened after I moved to the United States. It's not specifically to do with the U.S., just that I put an objective distance between myself and India. That hypervigilance eased a bit. For the first time, I felt that I had a reprieve from thinking about my caste.

One of the reasons that many Dalit people don't talk about caste in India is because they're certain that in these societies where upper castes are dominant, they would be mocked. But here, it was different.

In your book, you write about Rohith Vemula, a student and aspiring scholar from the Dalit caste who killed himself in 2016 at age 26, leaving a letter that said he was bullied at his institution and that "my birth is my fatal accident." You mention how deeply this letter affected you.

That came as a clarion call for Dalit rights in India. It enraged many of us. It made us question our own caste identities. I decided then I could use my voice for good to educate many people about caste. And that's what I did with this book.

Does caste present itself differently in the U.S.?

Here, we have to convince people it's not something that existed centuries ago.

Dalit people in Indian American communities in the U.S. have talked about discrimination in their own communities. We had a bill passed in Seattle, Washington, in 2023 — it became the first state in the country to outlaw caste discrimination.

Navigating a male-dominated society is challenging for many Indian women. You mention in your memoir how much more of a challenge it is for Dalit women.

Dalit women are doubly affected both by their gender and by patriarchal [discriminatory] structures that can be particularly contentious. Dominant caste men will think of Dalit women as untouchable and impure, but often objectify a Dalit woman at the same time. That leads to sexual violence in spite of calling them untouchable.

How do you rise above this kind of discrimination?

It can't be done overnight. This is a daily and constant struggle.

If you are constantly told that you are untouchable and unworthy ... to overcome that takes a lifetime of work and effort. You can't put your mind to it and overcome it, that's not how it works.

So some of us are lucky and have the chance to reject this. My grandmother didn't have that choice.

Kamala Thiagarajan is a freelance journalist based in Madurai, Southern India. She reports on global health, science and development and has been published in The New York Times, The British Medical Journal, the BBC, The Guardian and other outlets. You can find her on X @kamal_t

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.