It’s been 150 years since the U.S. Army forced the Navajo and Mescalero Apache to walk 400 miles to a prison camp in eastern New Mexico in an attempt to wipe out their culture.

“Just to walk the grounds a lump in your throat like something bursting forth and I felt all the anguish of the ancestors,” says artist Shonto Begay.

The impacts of the Long Walk are still felt today.

So many Navajos, like musician Clarence Clearwater, have moved off the reservation for work.

Clearwater performs on the Grand Canyon Railway — the lone Indian among dozens of cowboys and train robbers entertaining tourists.

“I always tell people I’m there to temper the cowboys. I’m there to give people the knowledge that there was more of the West than just cowboys,” Clearwater says.

Clearwater retraced his great-great-great grandfather’s footsteps 50 years ago for the long walk’s 100th anniversary. Along the way he learned this song, which translates, “I’m going home. It’s a long ways but I’m happy I’m going home.”

“When we were on that long walk that was a song that I heard all the way over there and back. It was very powerful,” Clearwater says.

Clearwater says the stories he heard as he walked are haunting: A Navajo family gave away their baby to a non-Native family, so the infant would have a better chance at survival. Many drowned crossing the Rio Grande.

“Some of the older people were talking about how elders like themselves had just been left out in the desert — left where they fell,” Clearwater says.

“The consequences of the Long Walk we still live with today,” Jennifer Denetdale says.

She is a historian and a University of New Mexico professor. She says severe poverty, addiction, suicide and crime on the reservation all have their roots in the Long Walk.

“So I think it’s really been a struggle to believe in our own ability to create on the Navajo Nation institutions and structures that will bring about prosperity and a way to live well,” Denetdale says.

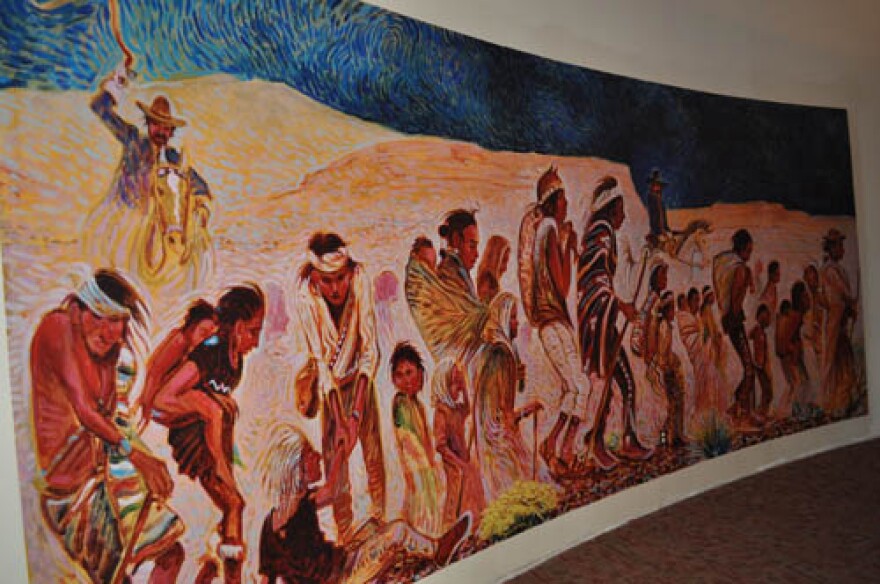

They walked to Fort Sumner, which was essentially a prison camp where Colonel Kit Carson attempted to “tame the savages.” Today a giant mural there commemorates the Long Walk. On one panel swirls of red and orange — the desert heat, a long line of families, a child on his mother’s back, a fallen elder, his son helping him up, behind them a soldier on horseback cracks a whip. Navajo artist Shonto Begay painted the mural.

“I could feel and hear the cries of the people; the trail, the heat, the cold. Just to walk the grounds, a lump in your throat, like something bursting forth, and I felt all the anguish of the ancestors,” Begay says.

The Navajo culture is intrinsically tied to the earth. Begay says many live or frequently return to the place where their umbilical cords are buried.

“When your umbilical cord is buried in the earth and it’s held by the earth and you know it’s held by the earth and you know the ground where it is, you feel at home and welcome anywhere in the world,” Begay says.

The Long Walk was among many attempts by the federal government to wipe out Native culture. Others include sending Native children to boarding schools to eradicate their traditions. Begay says he was 5 years old out herding sheep when a man driving a flatbed truck gave him candy and hauled him away.

“I grew up with a different name, a government name: Wilson. There was a lot of dead presidents and generals. In the early 1980s I reclaimed my great grandmother’s name, Shonto,” Begay says.

Shonto: It means “light dancing on water.” It is also the name of his town, his home where he remains connected today.

He wants his children and grandchildren to know their ancestors’ suffering and determination meant something.

“You know hey, your forefathers survived. Make something of it. Honor it,” Begay says.