Today is the deadline for the Trump administration to reunite thousands of migrant children with their families after being detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The Justice Department says it’s unlikely that deadline will be met.

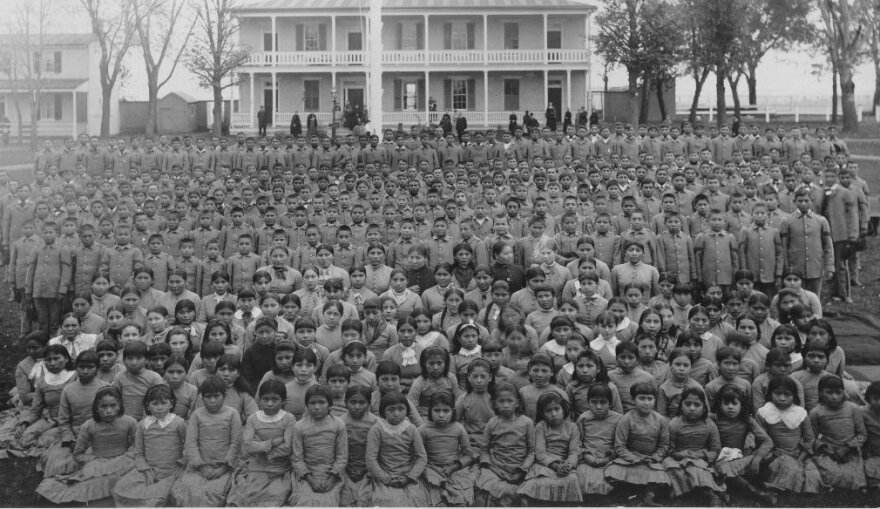

The separations remind Navajo artist Shonto Begay of another time in U.S. history when children were taken from their parents. As a 5-year-old he was one of tens of thousands of Native American kids seized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and forced to attend boarding schools. Most of their parents had no idea where they were. Though he was eventually reunited with his parents, he says the trauma of separation lasts a lifetime and he’s worried about these children.

Shonto Begay: I feel a lot for the kids, young kids that are being taken and living in cages today in various camps all over. And I’m sure these kids are feeling the same way—taken from their world from their language, and stuck in strange cages under Mylar blankets.

I think it was 1960 or ’61, I don’t really recall. But on a very hot autumn day, I was out herding sheep and I saw this strange contraption coming at me, way off in the distance in a cloud of dust. It was a truck, a flatbed truck. And in there was two people, an Anglo guy and a Navajo guy. And, they seemed nice, they came out and they asked me to come over and I came over off my donkey and they offered me a lollipop. And I went with them, and it turns out they were BIA people out collecting little Navajo kids to be sent to the boarding school.

Our parents, of course, were never notified. Kids were being taken from the back of sheep camps, they were being practically kidnapped.

We were forced to learn how to speak English. We were forced to worship another god, another way. And every time we’d go anywhere there was a sign, there was a mantra: “Tradition is the enemy of progress.” And in this manner, slowly, our own language, our religion, our world view, our mythology, our stories, songs, were being forced out of us. We were told that our culture was something we need to shed, and we need to become Anglo. Being at boarding school deprived me of knowing more of my own sense of identity. It also made you to some degree, I guess, despise yourself, who you are.

I remember, the overseers coming around at nighttime, at late night, making sure that everybody’s asleep. And if you were unfortunate enough not to be sleeping, your eyes open and they knew that you were awake, you were jerked out of bed, and you were forced to stand outside. I remember standing outside in my bare feet in the snow. One constant thing I remember is hearing a little child, a boy, crying somewhere in the dark.

I do not believe the government has ever apologized for the BIA boarding school experience. What it really was, it really was an ethnic cleansing experiment.

A lot of us, traumatized, and a lot of us fell by the wayside due to suicide, alcoholism, drug addictions, and just violence. As far as I know there’s only a few, handful of us alive today. We lost so many of my peers along the way because of the experience, of the separation of families.

At least we knew where our parents were. We knew eventually that we were going to be back, and the U.S. government told us it’s good for us, and the church told us that Jesus loves us.